In a day and age where elected officials are banning ethnic studies and attempting to further re-write history, augmented reality app Kinfolk is working to reclaim it.

Established in 2017, co-founder Idris Brewster launched a campaign to remove the statue of Christopher Columbus in Columbia Circle in New York. While in 2023, we’re well aware of the Spanish colonizer’s heinous actions and have gone so far as to refer to the anniversary of his arrival to America as Indigenous People’s Day, his legacy lives on through monuments in some of our country’s most populated cities. As marginalized and underserved communities continue to endure systemic oppression, whether it be through voter suppression or kicking children out of school because of their hairstyles, holding onto physical symbols of that oppression will only keep us in the past and delay meaningful change.

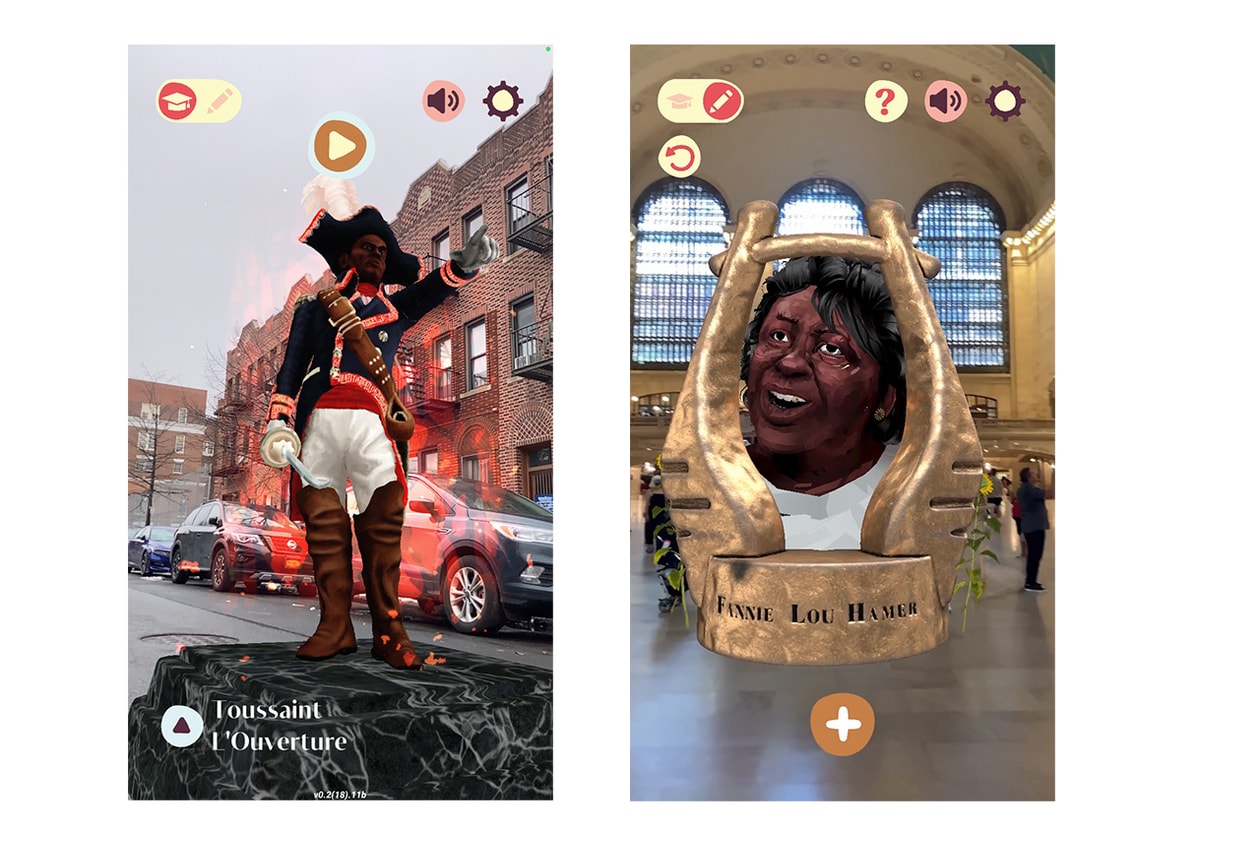

History has long since been written by the victors, skewing our collective narrative to one that largely leaves out the voices and experiences of others. Seeing ourselves as champions and owners of our stories is vital to understanding our past and moving more confidently into our future. Using its innovative technology to uncover virtual monuments wherever you are, Kinfolk lives up to its name, creating a sense of connection and community with an otherwise unknown ancestral history.

Most recently, the platform hosted an immersive installation, Land of the Blacks at the Tribeca Film Festival, enabling visitors to uncover previously lost stories, humanizing Sojourner Truth by stripping her of the white gaze, while introducing other hidden figures.

Continue scrolling to learn more about Kinfolk and hear from co-founder Idris Brewster below.

What initially sparked your interest in using technology to uncover Black and brown histories?

For me, it was the lack of agency that I felt with the loss of that history and not having a real way to recover that and share it with others. It started out in 2017 as we were trying to advocate for the removal of the Christopher Columbus monument. We would bring folks together and provide augmented reality experiences for people to see the true story of Columbus, as well as other heroes we wanted to represent instead. What ended up happening was that the city, which was determining at the time, whether they should remove the monument or make a landmark, decided to keep it and make it a landmark and so for us, it was a defeat, but it also showed us that we can’t really wait for our government to take action. We have to figure out a way to do it ourselves and not have to rely on others. There’s an infinite amount of lost history from Black and brown communities that needs to be uncovered, especially in America. Technology allows us to close the gap and better preserve, as well as, archive our history. With AR, we can share it in a way that’s fun and exciting because it creates a way for people to learn about these histories and have access to them without having to pay or wait for cities to create monuments. Kinfolk is all about taking it into your own hands.

Why is it so important for certain groups to reclaim their history, as well as play an active role in that process?

It’s incredibly important because our collective consciousness plays a large role in our actions and what we are building and doing. Right now, America is void of perspectives from Black and brown communities, in a very tangible way, as spaces in New York City are becoming more gentrified, losing the reminders of what was there. That’s why we have people coming from outside of New York into places like the Bronx and Brooklyn and not respecting those areas and making TikTok videos of how awful bodegas are. There’s a loss of respect and community within New York City, especially and other gentrified areas. It doesn’t allow us to move forward in an equitable way if we can’t put the pieces together around our past into our present. I think we’ll just repeat the mistakes of our past. People will doubt the impact of representation, but having voices uplifted to a large national and global stage, it’s so important to be able to achieve the change happening on a local level and in cities around the country.

Because the country is further banning these histories, that’s all the more reason to steward and shepherd our history together.

I really feel that to start, we need to be able to preserve our history so that we know where we came from so we can move forward in a better way. People always say history is boring, but that’s also if we think about it from a white Eurocentric perspective of written history. But what about the dynamic ways in which Black and brown folks have captured history? That’s through the way we moved, Black girls’ hand games, which is now imbued in every part of the culture, not to mention, oral storytelling. The technology is also important because we can create videos that result in a more engaging, animated experience. Up until this point, it’s been hard to do that in a way where people can feel immersed in history, but I think that’s why AR is so crucial because it can really capture that dynamic lived experience of Black communities that maybe haven’t been respected in the ways that archives have been built in the past.

Can you see the tangible effect Kinfolk has had in reclaiming history and actively playing a part in its uncovering?

I was demoing Kinfolk at a festival the other day and there was a group of five year olds who were just fighting over the iPad and engaging with it and it was the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen. So that was really exciting for me, but I do think there is a hesitancy because this technology hasn’t been built for us. White people have largely been the ones building these platforms. Unless you build your own complex website, people are putting these archives on Instagram or TikTok, but should we trust them with that precious community data? I don’t think so.

There hasn’t really been a platform out there that Black and brown folks, specifically, can trust to respect their histories. Having a Black-led platform can really create a space where we can build trust with the communities that we work with. Technology should be an opportunity to rewrite the inequities of our system and our world, but that’s not at all how it’s being used right now. Kinfolk is trying to be an example of how we can imbue more culture and equity into the systems that we’re building.

Could you share the inspiration behind your recent installation, Land of the Blacks at Tribeca?

As a person who’s building technology, if I think about my personal relationship with it, I’m trying not to be on my phone for five plus hours a day. I’m trying to connect more with nature. We use a tree stump as the anchor and basis for our AR monuments, using Kinfolk as that bridge between the physical and digital worlds. That’s why it’s important for us to build out an experience that connects people with their land and their environment, as well as with one another. When you’re at Tribeca and you see the installation, there’s four or five people that have their iPads, they’re all walking around the center altar and it feels like a community-based experience.

As we’re moving forward with Kinfolk, we’re going to build in more ways for users to not only to experience an installation, but to be able to add their voice as a mark into the spaces. That way, when people come and experience a monument, they can see the present day reactions, thoughts and experiences of folks who visited that space.

How important is community to the Black and brown historical narrative?

I think individualism is an inherently Eurocentric thing. The collective is always how my family has thought. I think if we go back to Africa, it was always a collective experience. With our monuments, we specifically work with community members on them. It’s not just about creating these monuments and putting them out there and having people react to them. It’s about getting people involved in that imagination and creative process from the jump.

Community is usually also defined in geographic terms, but our struggles are common across the world. It’s really something empowering for me to see the work that we’re doing at Flatbush and have someone in Taiwan or Mozambique or another country experience it. With a digital sculpture aspect, you don’t necessarily need to speak English to be able to maybe understand some of our monuments, so being able to connect folks and communities across borders is paramount. I think at the end of the day, it is about boasting up our own sense of collective consciousness. Because the country is further banning these histories, that’s all the more reason to steward and shepherd our history together.

No comments:

Post a Comment