Following a surge of protests after Black Americans died at the hands of police, Black advocacy groups such as the Black Lives Matter movement are now turning their focus on economic and education justice in 2021. According to MarketWatch, the BLM network raised over $90 million USD in 2020 and will use these dollars to further help Black communities amid the impact of COVID-19.

Following a surge of protests after Black Americans died at the hands of police, Black advocacy groups such as the Black Lives Matter movement are now turning their focus on economic and education justice in 2021. According to MarketWatch, the BLM network raised over $90 million USD in 2020 and will use these dollars to further help Black communities amid the impact of COVID-19.

When it comes to education, schools still remain heavily segregated by race in ethnicity even though it’s been over six decades after the Supreme Court declared “separate but equal” schools to be unconstitutional in the Brown v. Board of Education case. According to a 2017 study by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, Black children are five times as likely as white children to attend schools that are highly segregated by race and ethnicity. Moreover, Black children are more than twice as likely as white children to attend high-poverty schools. Race and poverty are intertwined in America, and the performance of Black and PoC students ultimately suffer when they attend high-poverty schools.

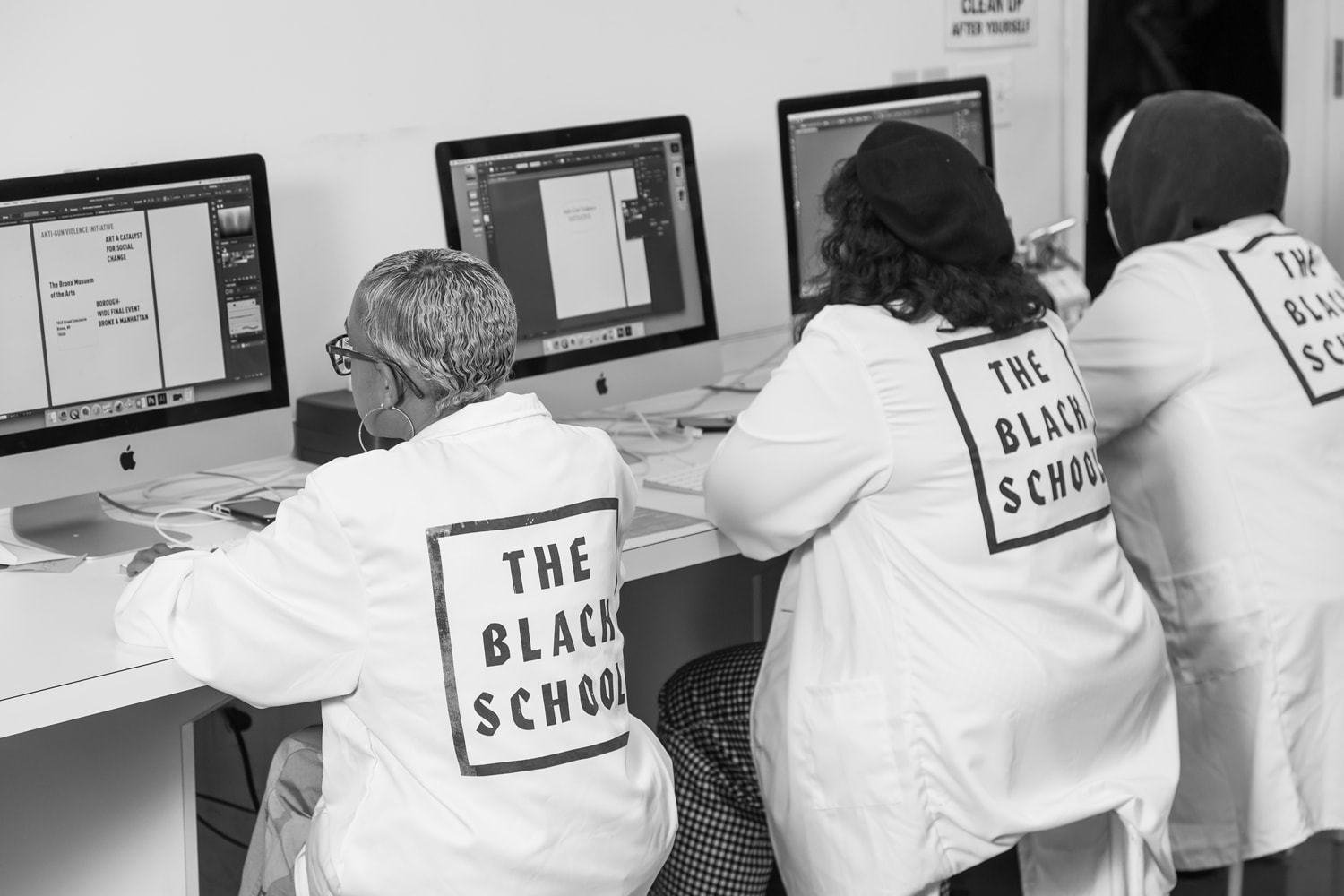

In order to facilitate a shift away from the ongoing pattern of heavily segregated schools, there needs to be services and contributions that would help close the gap between Black and white students alongside heightened awareness of racial injustice in schools. One of the emerging non-profit organizations championing radical Black arts education is The Black School founded in Harlem by Joseph Cuillier and Shani Peters. The organization fuses art-making workshops with presentations and group discussions on radical Black political theory. Their students also create collaborative site-specific projects that shed light on community needs. The Black School was initially inspired by community run schools founded throughout Black American history — spearheading proactive initiatives the Freedom Schools of the Civil Rights movement and The Black Panther Party’s Liberation Schools during the Black Power movement.

Paper Monday, Shani Peters And Joseph Cuillier, 2019, Digital Photography, Courtesy Of The Black School

“Black Love Fest is for everyone that genuinely loves Black people.”

The Black School exists as a three-part ecosystem: the School, the Festival and the Studio which is the organization’s in-house design firm. The multi-genre art and activism workshops help elevate the student’s knowledge of their own neighborhoods and communities as they also create work that addresses community needs. At the end of each year, The Black School hosts their own version of a Black Love Fest to publicly display work by the students while inviting professional artists, musicians and “anyone from the public who genuinely loves Black people,” said the founders. “The festival is our way of demonstrating a world that is centered in Black love- not tolerating Black people, or seeing Black people as a problem, but a world that honors Black people, and expresses gratitude, love, and care for Black people.”

Lastly, the organization’s youth-staffed design firm enables students to be further mentored in design and creative direction while providing students workforce training and real0-world client work. “We know that making socially engaged art for your communities is necessary, it is at the core of what we do, but we also have to acknowledge the real economic challenges facing our community. So, the studio helps us to directly address that need and also bring in earned revenue to support the school.”

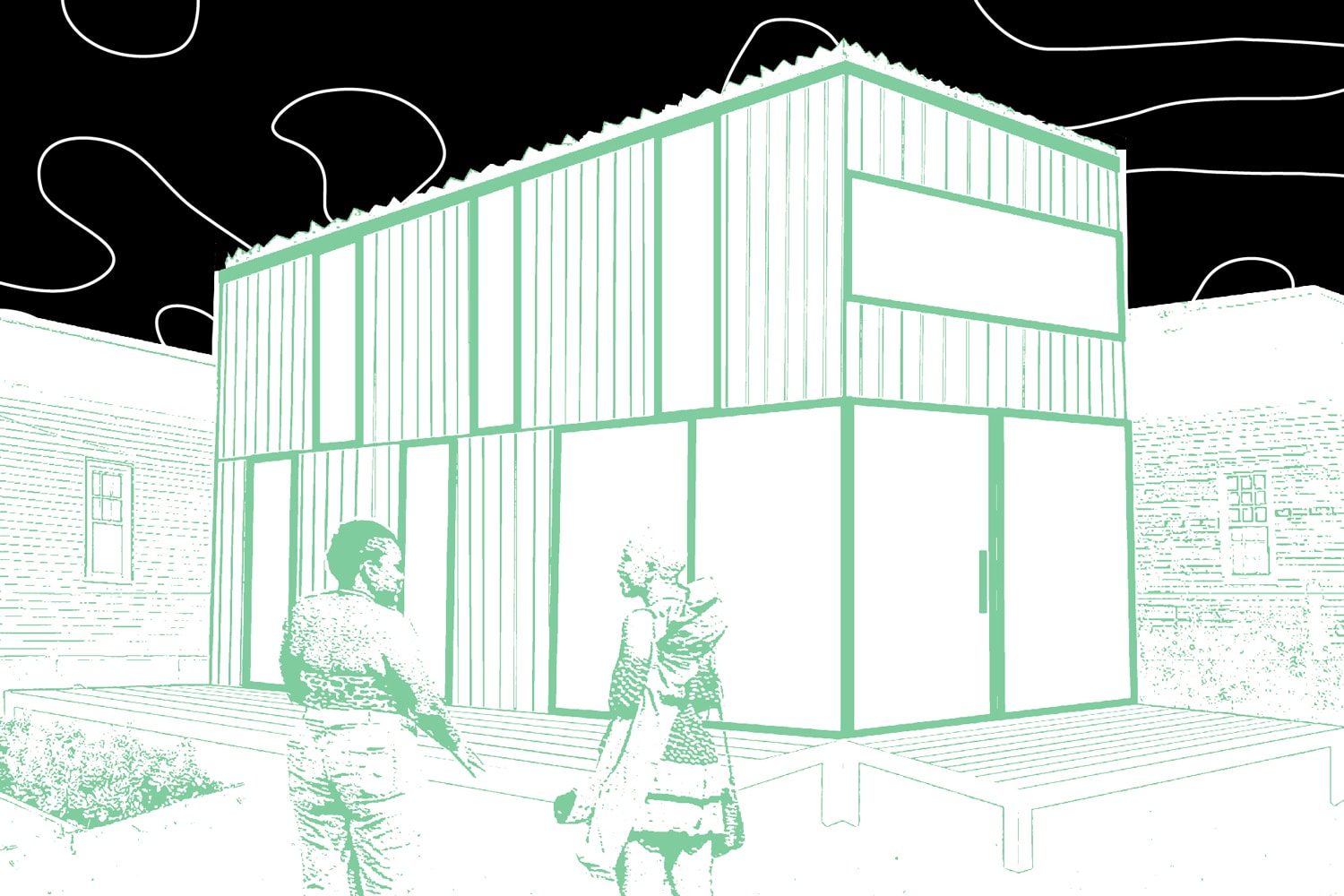

We reached out to Joseph Cuillier and Shani Peters to learn more about The Black School, their professional art backgrounds and upcoming initiatives they are working on — such as building an actual Black Art Schoolhouse, in New Orleans, to teach radical Black arts education which the pair have set up a GoFundMe page for contributions. Check out the exclusive interview below.

Dominique Sindayiganza, The Black School: Studio Portraits, 2019, Digital Photography, Courtesy Of The Black School

What were your main motivations for starting The Black School?

Joseph Cuillier: The idea first started to bounce around in my head in grad school as a response to my experience there. This was during Trayvon. For me, it felt like this perfect storm of all these things that culminated in me being more and more dissatisfied with the white-male-neoliberal-centric emphasis within art and design education. So for my thesis research, I was looking at social criticism, and how different liberation movements were using design to push their message forward. Around that time I was also reading bell hooks’ Teaching to Transgress, and learning about different Black community-led schools like the Panther schools and the SNCC Freedom Schools. That led me to start fantasizing about this idea of a radical Black art school that would take the theories and tactics of those movements and that emphasis on political and civic education, and pair it with socially engaged art and design. So, I think that all led to what came to become The Black School.

Shani Peters: While he was doing that, I was pursuing an art practice and teaching. I loved teaching and I had this dream in the back of my mind of creating my own community art space. I wanted that but was also overwhelmed with the idea of doing it on my own so when I met Joe I understood his vision and saw clearly how it fit with my own. It also helped that we’re both the children of educators. My dad taught Black Studies in Michigan for 50 years, and that played a huge part in how I was raised, and helps me navigate as an adult this cyclical relationship between art-making, teaching, and Black history.

You both have such distinct backgrounds in art, can you tell us about your respective artistic journeys?

JC: I came to art making and design through graffiti. I was in undergrad and putting up tags around school and it was catching people’s attention. So, the school newspaper started writing about it and essentially said “Stop, before you get arrested.” It sounded like good advice at the time, so instead I started putting the designs on graphic tees and that’s how I came to really fall in love with design. I started reading about the Bauhaus and the International School and decided to go to grad school to study design in what was a very interdisciplinary design program. So, as someone who entered art making through, first, street art and, later, graphic design, I am especially interested in public art and its capacity to widely distribute ideas without relying solely on the traditional museum/gallery system.

So, my project isn’t about any kind of medium specificity, but whatever the best way to get the idea out into the world. I am first and foremost dedicated to art’s transformative potential, its ability to facilitate social interactions and, ultimately, social change. My work currently centers on activism, Black radical politics, ritual, architecture, and fashion. Sometimes my work looks like object making, but a lot of the time it looks like getting people together and exchanging ideas.

SP: I didn’t recognize art as a career opportunity as a young person. I studied Communications at Michigan State then went to work for the City of Detroit. I realized I couldn’t do the rest of my life in office and started returning to making things the way I had as a child. I started studying art on my own, built up a portfolio and applied to grad schools. I thought on the other end I might be able to do more interesting admin work for an arts org but wound up getting a residency straight out of CCNY in 2009. I’ve been exhibiting and traveling via my art ever since but that never paid enough so I started teaching early on to subsidize my life. A lot of artists make a way with this balance but I realized right away that I really enjoyed teaching and that it fulfilled things for me that a solo practice couldn’t.

Both my teaching and my art have always pivoted around access. Figuring out how to make sure my work gets to people that don’t see themselves as ‘the art world set’. That set was never made visible to me growing up and I might have missed my chance to do my work and simply engage my own imagination if I hadn’t navigated (very often in the dark) my own way to the art world. My art overlaps many mediums and investigates activism histories, community building, the balance of wellness within politicized lives, and the creation of accessible imaginative experiences.

Dominique Sindayiganza, The Black School: Studio Portraits, 2019, Digital Photography, Courtesy Of The Black School

“Our youth culture is the most powerful on the planet. A Black person turns their hat backwards and the whole world turns their hat backwards.”

You both are teachers of radical Black arts education. What are the benefits of art exposure to the youth, especially in the Black community?

SP: Most Black people who are exposed to our history in any depth get that information either from a dedicated family member or later in life if they are fortunate enough to find their way to a college Black Studies course. The foundations of our awareness definitely come from our families, and absolutely have fortified us to be able confident, well adjusted people. There is a deep well of inspiration to be pulled from African diasporean art and culture, from our political histories, and from the overlaps of the two. We pull from that well in our own work and design creative structures for others to do so too through The Black School. There have been Black educators all over this country for years who recognize these same needs and benefits. We are continuing and expanding on those legacies

JC: Our youth culture is the most powerful on the planet. A Black person turns their hat backwards and the whole world turns their hat backwards. America’s number one export is our culture, and a lot of that starts in Black youth culture. So, what happens if we harness that culture for the purpose of Black revolutionary politics? Everybody is getting rich selling our cool. You’ve seen what Black folks can do with a turntable or athletic show. What can we do with a 3D printer or a laser cutter or a tufting gun or a room full of iMacs or a 5D?

We’re living in an unprecedented time where there is heightened awareness on racial inequality alongside the COVID-19 pandemic. How has your organization navigated this period?

SP: The beginning of the pandemic was as deflating and debilitating for us as anyone. Especially being in NYC and being parents to a young child, there was so much fear and complete disruption of our life and plans. We experienced our own loss and still feel the collective sense of grief deeply. We shifted the engagements we were already in the midst of to remote structures but really had little desire to reinvent our work as exclusively online programming. For all those challenges, canceled plans, and continued loss of Black life at the hands of police, we were ecstatic the night Minneapolis brought the country to its feet. The next night 25 cities were engaged in organized protest.

In so many ways the uprisings have lit a fire for us and for people to support us even through these insane times. We collaborated on some beautiful remote workshops with ReThink NOLA, had quite a few public talks, and have taken on new clients to TBS:Studio but for the most part have used this time to plan and build towards the future we want. We also spent a lot of time teaching university courses to save up and cover our personal expenses for making the big move down to New Orleans that is finally happening now.

Black Love Fest Htx 2019, Bria Lauren, 2019, Film Photography, Courtesy Of The Black School

“Our Blackness and our respective experiences within it have been preparing us for this work for our whole lives and give us all the tools and motivation we needed to grow this work.”

What are some of the hardest obstacles you’ve faced since you started The Black School in 2016?

SP: Some of the hardest parts go hand in hand with the easiest part. Our Blackness and our respective experiences within it have been preparing us for this work for our whole lives and give us all the tools and motivation we needed to grow this work (i.e. knowledge, resilience, purpose). The other side of that is the way western society bristles against Blackness. That means always having to be more qualified and precise in your planning than white counterparts competing for the same resources. Even with the deep resumes, we bring to our work, we have regularly been underestimated and under-appreciated for our effort. That happens from world-renowned museums to public schools. In our first year of working we planned to work long-term with one, thoughtfully selected Brooklyn high school. But within a matter of weeks, it was clear the school was giving minimum support to ensure the program’s success. We had a sizable grant funding that programing and were not about to let it go to waste on a partner that wasn’t committed. We wound up reorganizing our first 10 sessions set for one location into 16 or 17 sessions across at least 10 locations. So very early on we learned to adapt and shift plans on a dime. We’ve also learned to always advocate more for ourselves and our community than we’ve been conditioned to expect.

What are you hoping to accomplish with this physical space and what sort of initiatives are you looking to establish?

JC: In the past three years, we have served almost 400 students, facilitated 100 workshops and classes, produced three Black Love Fests with 3,000 attendees, trained and employed 16 design apprentices, and partnered with 50+ organizations and 40+ professional artists. So with these successes under our belt, we want to expand our efforts into daily art+activism educational programming, and add a gallery, library, meditation room, artist residency, art+design studios, digital maker space, and urban farm. Ultimately, a physical space will allow us to put down deep roots in a local community, which will allow us to have an concentrated as opposed to disperse impact and extend the legacy of innovative education alternatives that are centered on Black love, self-determination, and wellness for the benefit of an entire community.

The Black Schoolhouse Concept Sketches by Shani Peters And Joseph Cuillier, Digital Illustrations, 2019, Courtesy Of The Black School

“Take care of your community and when the time comes your community will take care of you. We are living proof of that.”

What advice would you give to aspiring artists of color?

SP: Be yourself. Relentlessly be about what feels the most genuine to you and eventually it will become clear to others (and you) what your unique gift and purpose is. Be curious. Travel whenever you can. Like I tell my 4-year-old, be bold and be brave. And consult the ancestors. They’re with us and they are b a d a s s.

JC: Take care of your community and when the time comes your community will take care of you. We are living proof of that. We had this idea for a while now and we had been writing grants and getting told “No”. But as soon as we brought the idea to the people with our track record to back it up, they lifted us up to the point that the foundations were coming to us. So, please really think about who your audience is. You don’t have to make work for the typical person that goes to the museums and galleries. If you’re creative, use your creativity to come up with solutions for issues in your community. Live for the people and there’s literally nothing you can’t accomplish.

No comments:

Post a Comment