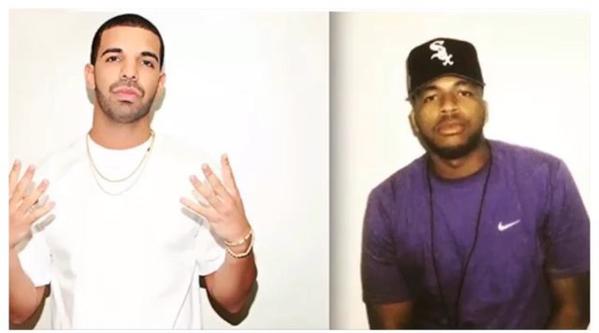

Quentin Miller has decided to break his silence and spoke on the allegations that he ghostwrites for Drake.

Winter 2014… I was just another guy working a job he hated with a passion for music…. And somehow found myself on the phone with One of my idols.. I told him i worked in a bakery and his exact words were “F*** that, your destined for greatness”… Hearing that from someone that I’ve been studying since 2009, bar for bar…. Theres no way to describe that..

Most of the project was done before i came in the picture.. i remember him playing it for me for the first time thinking “Why am I here?” like.. what does he need me for??

The answer is.. Nothing…

I watched this man piece together words in front of me… I watched him write/ replace bars 2- 3 at a time on 6pm in NY.. I witnessed him light up, go in and freestyle madonna…. I took notes from the best in the game….

I remember him Showing me the thank you notes in NY before the album dropped.. Showing me the QM, telling me they put me on the credits (Ghostwritter???) … He attached my name to something that touched the world.. When nobody would pay attention, drake saw something in me and reached out… Of all people… drizzy.. Two artist in exact opposite spaces in their career.. We came together and made something special..

I am not and never will be a “ghostwriter” for drake.. Im proud to say that we’ve collaborated .. but i could never take credit for anything other than the few songs we worked on together ..

Thats all i have to say on it.. back to this 1317 s**t…

– Q.M.

ATLANTA —

On a late night in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward, lots of people were leaving and going to bars. Out there on the side of the street was Gary Jerkins of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation. He was standing in front of a large HIV testing van.

“Get tested! Get your result in one minute,” Jerkins shouted as people passed him. “Participate. Raise awareness.”

Jerkins passed out condoms and candy.

“So, we pass out lifesavers and we tell people that the test can be a lifesaver, he said. “We pass out dumb dumbs and we say don’t be a dumb dumb. Know your status. And we pass out Smarties. Smarties get tested. Know your status.”

Jerkins says every status is good whether positive or negative if it means halting the spread of HIV. Atlanta is the fifth highest metro area for rates of new HIV diagnoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“In many ways the South is the epicenter of the epidemic and really Atlanta is the epicenter of that,” said Nic Carlisle, executive director of the Southern AIDS Coalition.

LaMar Yarborough, 23, remembers his diagnoses. It was on his 18th birthday. A couple days earlier, he had been rushed to Atlanta’s Grady Hospital.

“Two days before my birthday, I fainted in the shower,” Yarborough recalled. “And my mother, she rushed me to the hospital. I went to doctors, and I had everyone standing around me. You know, Grady partners with Emory. So, you know you have a whole bunch of medical students. So, it was like eight people around me you know asking me questions. They told me I had AIDS, and then they were asking me if I knew what that is and things of that nature. At the time, I did not.”

Yarborough said the virus was sexually transmitted. At the time, he was sleeping with both men and women. He also developed a type of cancer tied to HIV. Yarborough said within his family, talk about sex was confined within heterosexual relationships. Sex Ed in school wasn’t much better.

“Pretty much within the south we do an abstinence only teaching,” he said. “If you were to catch an STD, I remember the video, it was like the steam rising from the ally, the girls with the short skirts on, guys with the sagging pants. I remember friends and I we kind of checked out cause that’s not us. We talk proper. We do what we’re supposed to do. It just didn’t apply to us.”

Now he is more vocal about the importance of being able to identify with someone on how to handle HIV.

“You don’t have a lot of people who are advocates who are African American men that I’ve seen growing up,” he explained. “We are dying from this and therefore it makes me step up to the plate and say I need to be a leader, and to educate my fellow people of color so that we don’t die from this epidemic.”

Death from AIDS is still a reality for many young African-Americans. Dr. Abigail Hankin-Wei oversees the H-I-V testing program at Grady Hospital, where Lamar Yarborough was diagnosed.

“We’ve had patients who were diagnosed on the same-visit that they died of their complications, which is not the way we should be doing it in 2015,” she said.

Hankin-Wei said at Grady, there are anywhere between 15-and-20 new HIV diagnoses a month. In about half of all cases, the patient already has AIDS, which she says for some patients can take about a decade to develop.

“We do have the patients that despite the possibilities of treatment are going to get diagnosed extraordinarily late and too late to get the benefits of treatment,” she noted.

According to the CDC, the South has the greatest number of people living with the disease and dying from it, and that in Georgia, 613 people died with AIDS in 2012. Emory researcher Patrick Sullivan used to oversee HIV surveillance at the CDC. He said black men who have sex with other men in Atlanta are three times more likely to become HIV positive than whites. That is despite having a similar number of sex partners.

“That finding was related to two things,” Sullivan explained. “One was the racial composition of their sexual network. In other words, they had more black partners. Those black partners were more likely to be living with HIV, and the other was access to health insurance.”

Medicaid is the largest source of coverage for persons living with HIV/AIDS, said Nic Carlisle of the Southern AIDS Coalition. Carlisle said not expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, which is the case in Georgia, keeps some people from getting tested.

“The bigger issue and I think the bigger issue where Medicaid comes in is so many people are being diagnosed late,” he said. “I think that’s one of the signs of not having access to routine health care. Not being part of a culture that establishes a primary care doctor and encourages folks to have an annual checkup.”

For those already diagnosed with HIV, there is a safety net. It is the federal Ryan White CARE Act, and it’s available to people who are HIV positive and don’t have any health coverage.

“But that safety net is vulnerable,” Carlisle said. “It’s subject to appropriations every year and if and when the Ryan White Care Act goes away and Medicaid hasn’t been expanded, you’re talking about a disaster for people living with HIV in the south.”

LaMar Yarborough relies on the Ryan White CARE Act to cover the cost of his antiretroviral medication. He is unemployed and does not qualify for Medicaid in Georgia.

“For me just personally if Ryan White ever went away then hopefully God willing, I would be financially stable to pay for them myself,” Yarborough said.

Georgia’s Department of Public Health reports that a disproportionate share of the more than 50,000 people with HIV in Georgia who are low-income and black.

“If they don’t have enough money, for example, to put a roof over their head, they’re not going to spend a lot of attention thinking about taking the medication for HIV,” said Patrick O’Neal, the director of Health Protection for the Georgia Department of Public Health. “They’re going to be thinking about the basic needs of getting a roof over their heads. Poverty definitely plays a role, and obviously throughout the southeast we have severe poverty issues.”

Georgia is one of several states that’s part of a pilot program with the CDC to boost HIV testing and prevention, particularly among minorities.

Meanwhile, Yarborough doesn’t live out his days as a death sentence. He said he feels good. He is taking his medication and this summer started a support group to help youth and young adults living with HIV.

No comments:

Post a Comment